The Artistry of Teaching Yoga

Improvisation No. 30 (Cannons), Vasily Kandinsky, 1913, The Art Institute of Chicago, Open Access

The Artistry of Teaching Yoga

by Rebecca SebastianTo create something is an action. It is the process of bringing something into existence.

I remembered that as I lugged a very heavy box of smooth river rocks to the center of the room. That day, I wanted to explore the idea that if we were present enough, we might feel the subtle movements of some of the thirty-three individual joints in our feet. And maybe—if we noticed how our feet naturally shift to accommodate new terrain, new sensation, new surroundings—we could consciously bring some of that same adaptability to our brains and our hearts.

But it all started with river rocks.

What if teaching yoga is one of the most overlooked creative professions?

This moment points to a larger question within the artistry of teaching yoga:

What if teaching yoga is, in fact, one of the most overlooked creative professions?

Personal trainers have rules. They have goals. They have protocols designed to get clients from point A to point B. But yoga teachers often begin with something less concrete: a sense that something meaningful might happen. We hold an idea, a question, a felt experience, and then we work to let it emerge through the body.

We bring students—clients, humans—into fuller existence using our knowledge and the active attention of our minds.

Maybe yoga teaching really is an art form.

Student as Muse

I have spent a lot of time thinking about creativity in yoga teaching and yoga therapy, and one idea I find consistently under-discussed is the concept of having a muse. A muse, by definition, is a source of inspiration—and when done well, I believe our students are our muse.

We may arrive to class with an agenda or even a pre-planned list of movements we intend students to perform. But rigid adherence to a plan can quietly strip the artistry from the work. Our students, in the present moment, offer essential information about what should be taught and how it should be delivered. With practice, this responsiveness becomes almost instinctual. We don’t consciously decide to change course—it simply happens.

Our students, in the present moment, offer essential information about what should be taught

Naomi has back challenges? We adjust.

Bruce feels low? We meet him there.

There is beauty—and artistry—in this exchange: in the co-creation of something alive between teacher and student. Teaching becomes less about execution and more about relationships.

The Removal of the Teacher

About twelve years ago, I began intentionally bringing more creativity into my teaching. At first, I wanted students to see my artistry. I wanted them to know that this work was creative for me, not merely vocational.

But I soon realized that in order to truly see my students—and to support them in seeing themselves fully—I needed to practice removing myself from their experience.

If my goal was embodiment, then I had to stop positioning myself as the reference point. I needed to remind students that their bodies were present. That they were co-creators of the work.

Removing myself removed the ideal they were trying to live up to.

The first thing to go was home base. For many yoga teachers, home base is the mat at the front of the room—the place we return to in order to orient ourselves, and the place students look to in order to see if they are “doing it right.”

That familiar question—am I doing it right?—reveals something deeper. Somewhere along the way, we taught students that there is a “wrong.” That their bodies might be incorrect.

Removing myself removed the ideal they were trying to live up to.

It also allowed me to move freely through the space. I often found myself in corners or quiet edges of the room. Over time, students adjusted. They listened more. They relied less on watching me in an elaborate game of Simon Says.

What emerged is still my favorite thing to witness in a yoga space: students experimenting on their own, often without my verbal prompting, discovering what feels good in their bodies.

Removing me allowed them to become more luminous for themselves.

Co-Creation Is the Art

Responsiveness is how we co-create a class. Sometimes this means holding a theme or lesson while also recognizing that students arrived tired, frustrated, or emotionally overloaded. The work becomes a negotiation: how do we meet people where they are while still guiding them toward something meaningful?

Responsiveness is how we co-create a class.

This is the art of co-creation.

It gives me pause when teachers talk about sequences and playlists as the point of coming to class. People come for many reasons—chief among them, hopefully, yoga. Yoga as liberation. Yoga as a shift in attention. Yoga as embodiment of the truest self.

And sometimes, if we’re honest, the reason is co-regulation: the deeply human experience of nervous systems settling together. There is something profoundly comforting about relaxing in a room where everyone has been invited to do the same.

Recently, I read a post by someone with a large social media following lamenting how “rude” it is when students go rogue—ignoring cues or moving differently than instructed. The implication was that these students were missing the point.

Performance is a valid craft—but this isn’t that.

But if the point of yoga is presence, communion, and liberation, then isn’t it equally fair to say that teachers who ignore co-creation are missing something essential?

That approach feels closer to performance. And performance is a valid craft—but this isn’t that.

Yoga teaching is something else entirely.

Artistry and Branding

One of the tensions worth naming in this conversation is the growing pull between artistry and branding.

Many teachers pour extraordinary creativity into social media—carefully styled posts, clever captions, curated reels—while far less creative energy is directed toward the lived experience of class and studentship. As a profession, we’ve been given very little guidance here. It can be difficult to distinguish between what authentic yoga teaching looks like and what marketable yoga teaching looks like.

The danger isn’t visibility. It’s when creativity becomes representation rather than expression.

Creativity, at least the kind that sustains teaching, is often a quiet process. It requires introspection, inspiration, and ease. When that process becomes part of a visual content machine—measured in reach, engagement, and consistency—it becomes harder to discern where creative teaching ends and the branding of the teaching self begins.

This isn’t a moral argument against visibility. It’s an acknowledgment of friction. The skills required to build a recognizable brand are not the same skills required to sense a room, adapt a practice, or respond to the subtle emotional weather of a group of humans breathing together.

When artistry is pulled outward—toward constant performance—it risks losing the interior listening that makes teaching feel alive. The danger isn’t that teachers become visible; it’s that creativity gets consumed by representation rather than expression.

Staying Creative While Staying Fed

Talking about creativity as a yoga professional can feel unrealistic. “Give people what they want” is advice many teachers and studio owners hear repeatedly.

But our work—our practice—is about returning to yourself. And if there’s one thing more frightening than trying something new, it’s returning to yourself after a long time away. It can feel like walking into a childhood home where the furniture has been rearranged, the walls repainted, and an unforgiving overhead light flipped on.

So how do we reconcile creative expression with the very real need to get paid?

For me, the answer has been showing up as the teacher I want to be while adopting systems that make that possible.

The first time someone suggested I teach the same class Monday through Sunday, I thought I would lose my mind. At the time, I was teaching close to eighteen classes a week, and repetition felt unbearable.

I didn’t die.

Instead, it was some of the best advice I ever received.

Structure didn’t kill creativity. It gave it somewhere to deepen.

When we rely on co-creation, even a consistent sequence becomes endlessly alive. Each class responds to the people in the room. What I said about a movement or philosophical idea on Monday inevitably evolved—becoming more refined, more precise—by Sunday.

Structure didn’t kill creativity. It gave it somewhere to deepen.

Perhaps the invitation here is simple.

To trust yourself a little more. To trust your students a little more. To remember that teaching yoga isn’t about control or display, but about creating the conditions for presence to emerge.

You don’t have to be the most polished, the most visible, or the most impressive teacher in the room. You have to be available—to listen, to respond, and to allow something genuine to unfold.

When we let go of proving our value, teaching becomes lighter. More collaborative. More alive.

The art of teaching yoga isn’t what we show. It is what we make possible.

Georgia O’Keeffe—Hands, 1920/22 Alfred Stieglitz, American, 1864–1946, Art Institute of Chicago, Open Access

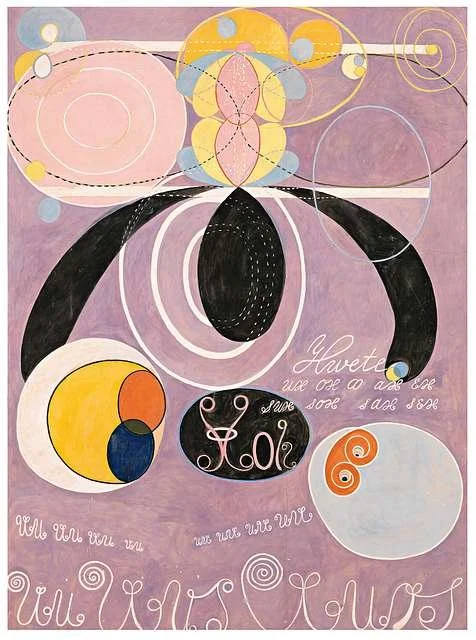

Hilma af Klint - The Ten Largest No. 6 - 1907